Honoring a Lifesaving Milestone

Paul Lauterbur developed MRI at Stony Brook

September 5, 2018

When Stony Brook University researcher Paul Lauterbur, PhD, created the first multi-dimensional image using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), he sparked a new age of medical technology and clinical care. His 1971 discovery made it possible to get a clear look inside the human body without surgery or x-rays.

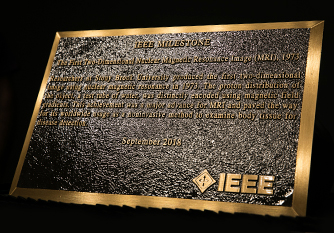

Dr. Lauterbur’s life and work were honored September 5, 2018 in a ceremony at Stony Brook Medicine’s new Medical and Research Translation (MART) building. Titled a “Milestone Dedication,” the event was co-hosted by the Long Island section of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and Stony Brook University.

Until Lauterbur, a professor of Chemistry and Radiology at Stony Brook University from 1963 until 1985, made a key modification in NMR’s magnetic field, scientists used the technology to study atoms and molecules. His achievements earned him the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, shared with Sir Peter Mansfield of the University of Nottingham in England.

Stony Brook University President Samuel L. Stanley Jr., MD, described how Lauterbur used the spatial information contained in NMR signals to make multi-dimensional pictures. Today MRI is widely used for research and early detection of severe conditions such as multiple sclerosis, osteoporosis and cancer, Dr. Stanley said. He called Lauterbur’s work “one of the most important medical discoveries of the twentieth century.”

Kenneth Kaushansky, MD, Senior Vice President, Health Sciences and Dean of Stony Brook University School of Medicine, told the audience that Lauterbur was taking a break and eating a hamburger when it occurred to him that he should use a non-uniform magnetic field for imaging. “He rushed out of a local restaurant so he could write it down in his spiral-bound notebook,” said Dr. Kaushansky.

“It may not be as well known,” he said, “but Stony Brook also developed the first PET imaging tracer, called FDG-PET, which today is widely used in clinical oncology.”

“It seems to me that his towering accomplishment came about, in part, because he had the ability to understand other disciplines, which include electrical and computer engineering,” Taub said. “This together with an insatiable curiosity and strong intellectual honesty is what he brought to bear, and we are the beneficiaries.”

Lauterbur’s daughter Elise Lauterbur – a doctoral candidate in Stony Brook University’s Department of Ecology and Evolution – said her father wanted to “instill curiosity and the drive to broaden not just scientific understanding, but the possibilities of scientific understanding.”

Lauterbur’s daughter Sharyn Lauterbur-DiGeronimo recalled that in the midst of his rigorous scientific endeavors, her father always made time to help her with homework or teach her how to throw a baseball. Lauterbur was a humble man, Sharyn said, one “who grew up on a farm, so he enjoyed life’s simple pleasures.”

NYS Assemblyman Steve Englebright said the development of MRI is an example of how much has been accomplished at Stony Brook University in the half-century since its birth.

Lilianne R. Mujica-Parodi,PhD, Director of the Laboratory for Computational Neurodiagnostics and Associate Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, said that because of Lauterbur’s work, imaging tools available to clinicians and researchers are able to reveal the current state of a patient’s brain. She compared MRI to GoogleMaps – information that tells us not only what is, but also what could be.

“MRI is a signal that’s changing in time,” she said. “It shows us not only who has a condition, but who will develop it.”

Tim Duong, PhD, Director of MRI Research and Vice Chair for Research in the Department of Radiology, spoke of Lauterbur’s vision.

“The way he would disturb the magnetic field in a deliberate manner, this was very different,” he said. “Because Paul realized that imaging does not need wavelength to be smaller than the object being imaged, everything now is possible. Now we can look within the body structionally and functionally.”

Stony Brook University will continue to advance Lauterbur’s vision, Duong said, and he predicted that in five to ten years, MRI technology will advance in many ways.

“MRI speed and spatial resolution will quadruple, so a comprehensive whole body MRI exam will take [only] a few minutes,” he said. “Some MRI devices will be portable. And MRI will be an integral part of treatment planning, in real time.”